Where did my assembly code go?

In my last post about pipelined processors and instructions I briefly talked about processor ports and how they affect instruction execution.

Let’s talk some more about the pipeline and its components. I’ll focus on relatively recent Intel architectures, namely Haswell and up - where some key architecture changes were introduced.

Processor architecture

Generally speaking, these processor architectures can be divided into frontend and backend.

When a program (i.e instructions and data) is ready to execute, the instructions make their way into the L1 instruction cache, located in the frontend.

The data is loaded into the L1 data cache, in its turn located in the processor backend.

From there, a lot of complicated and cool things start to happen.

The processor frontend

A number of complicated things happen on the frontend of the pipeline so I’ll summarize the most significant and relevant ones in the context of this post.

Here is where the instruction fetching and all the complex decoding happens. On most, if not all modern Intel processor, instructions are fetched at a rate of 16 bytes per clock cycle and put into an the instruction queue.

This is also where instruction macro and micro fusion happen; where the branch predictor, the stack engine, the loop stream detector (LSD) and the decoded stream buffer (DSB) live.

Quickly trying to explain some of these things, the LSD helps the execution of instructions in a code loop while the DSB contains already decoded micro operations.

The branch predictor is also an awesome optimization mechanism optimizes execution by, as the name says, predicting which branch the code execution will take. There are a number of things us developers can do to help the branch predictor and I promise I’ll write a full post about it one day.

At the end of all that is the decoded instruction queue or allocation queue, where all the micro ops are stored and then fed to the backend.

The processor backend

We can look the backend as two sets of components: the execution engine and the execution units.

The execution engine contains the register renaming circuitry, the ordering buffers and the instruction scheduler.

It turns out the registers we are used and have access to are not the only ones the processor can use. Internally, more registers can be allocated to accommodate data and instruction execution.

Together with the ordering buffers, micro operations can be executed more independently and in an order that can make use of the processor resources more efficiently. We’ll talk more about these benefits in the sections below.

Finally, from renaming to re-ordering, the instructions in form of micro operations are scheduled for execution and sent to the execution units appropriately. After the operations are executed, they are retired and removed from execution.

The remaining of the hard work happens in the execution units.

Here’s where all the addressing, arithmetic, vector operations, memory read/write and a lot more happen. Each processor core has a finite number of dedicated execution units, solely responsible for one particular task.

For example, the ALU (Arithmetic Logical Unit) as the name says, is responsible for all logical operations as well as summation and subtraction. The ALU is usually the most frequent unit in a processor core.

To illustrate a bit more, the Skylake architecture contains 4 ALUs, 1 integer multiplication unit and one integer division unit.

There are also unit specialized for floating point and vector operations.

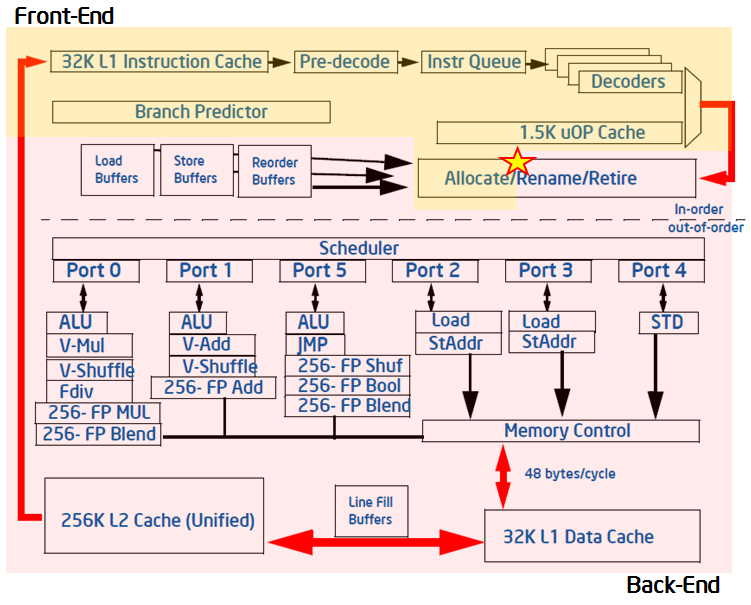

The image below depicts the backend and frontend parts of a generic architecture and while it should not be taken as the norm for all modern Intel processor, it does provide a better understanding of all the concepts we’ve seen so far.

(from Intel® VTune™ Amplifier 2019 documentation)

Out of order execution

We saw that on the backend, with all the micro operations in hand, the processor scheduler starts assigning operations to the processing units.

As we also saw, there is a limited number of processing units per function, which means a processor with only one vector multiplication unit cannot schedule two concurrent vector multiplications at the same time.

But what if it could execute another operation in a different processing unit while it waits for the vector multiplication unit to be available?

That’s where the out-of-order-execution (OoOE) technique comes in. Scheduled operations can be execute not in the order in which they were programmed (written by a person or compiler) but instead, in the order that suits better the data that needs to be processed.

IF the scheduler sees operations in the queue that have no data dependency and that can be executed in different units, it can schedule the operations for execution.

Given the fact that instructions (and consequently micro ops) have different latency (number of clock cycles required to execute), one interesting effect of that is that operations there were further down in the queue can finish before the first scheduled operations.

After executed, the operations are then reordered in the ordering buffers and then can be retired - committed or discarded. Operations (instructions really) are discarded if the speculative execution turned out to be wrong. Otherwise, the result of the operation is considered valid and committed.

Speculative execution is part of the branch prediction functionality I mentioned before and sufficiently interesting and complicated for it to take an entire new post.

Knowing the hardware helps optimization but

It is still hard. Trying to optimize the code to maximize the usage of the processing units or making sure the scheduler queue is always full can be very difficult and most of the time, unnecessary.

The main reasons for that are, aside from the fact microprocessors are very complex marvels, we have the compiler and the out-of-order-execution smarts specially designed to do just that. Compiler writers and processor designers do all the hard work so that, us the end users, don’t have to.

That said, we also should not make the processor and compiler work more difficult and there are things we can and must do to get the best of your hardware.

Facilitate auto-vectorization

This applies mostly to operations on arrays and matrices. If the compiler finds operations in an array can be done simultaneously, it will generate assembly code that uses vector instructions (MMX/SSE/AVX).

However, if the are data dependencies between elements in the array, the compiler cannot do much about it and it will generate the assembly using scalar instructions.

Here’s one example of a code that has data dependency

void calculate(){

const int length = ARRAY_LENGTH;

int weight[length];

int value[length];

int total[length];

// populate weight, value and zero total

for(int i = 0 ; i < length-1 ; i++){

total[i] += value[i]+weight[i];

value[i+1] = weight[i+1]-1;

}

total[length-1] += value[length-1]+weight[length-1];

}

The idea here is that on each iteration, an array accumulator is incremented with a value and a weight, and the value for the next step is set to the weight on the next step.

The code is intentionally simple and most likely not something you’d se in real life, but the dependency pattern can appear more frequently than one would imagine.

There is a clear dependency between one iteration and the next, preventing the compiler from vectorizing the code.

Below the pertinent assembly code for calculate()

0x100001e20 <+224>: mov edi, edx

0x100001e22 <+226>: mov eax, r8d

0x100001e25 <+229>: xor esi, esi

0x100001e27 <+231>: jmp 0x100001e4e

0x100001e29 <+233>: nop dword ptr [rax]

0x100001e30 <+240>: add eax, edi

0x100001e32 <+242>: add dword ptr [rbp + 4*rsi - 0x201c], eax

0x100001e39 <+249>: mov edi, dword ptr [rbp + 4*rsi - 0x4018]

0x100001e40 <+256>: lea eax, [rdi - 0x1]

0x100001e43 <+259>: mov dword ptr [rbp + 4*rsi - 0x6018], eax

0x100001e4a <+266>: lea rsi, [rsi + 0x2]

0x100001e4e <+270>: add edi, eax

0x100001e50 <+272>: add dword ptr [rbp + 4*rsi - 0x2020], edi

0x100001e57 <+279>: mov eax, dword ptr [rbp + 4*rsi - 0x401c]

0x100001e5e <+286>: lea edi, [rax - 0x1]

0x100001e61 <+289>: mov dword ptr [rbp + 4*rsi - 0x601c], edi

0x100001e68 <+296>: cmp rsi, 0x7fe

0x100001e6f <+303>: jne 0x100001e30

0x100001e71 <+305>: mov eax, dword ptr [rbp - 0x4024]

0x100001e77 <+311>: add eax, ecx

0x100001e79 <+313>: add dword ptr [rbp - 0x24], eax

0x100001e7c <+316>: dec rbx

0x100001e7f <+319>: jne 0x100001e20

Now let’s try to break the dependency. The strategy I’ll use here is quite useful and although it might not be obvious at first sight, it’s worth trying to get familiar with it.

We start by moving part of the first iteration out of the loop. Just the line that does the first calculation of total

total[0] += value[0]+weight[0];

then we shift the entire loop to start on the next iteration all the way to the end. Except the first set of instructions in the loop is not updating total but in fact recalculating value. This is what we have in the end.

void calculateVec(){

const int length = ARRAY_LENGTH;

int weight[length];

int value[length];

int total[length];

// populate weight, value and zero total

total[0] += value[0]+weight[0];

for(int i = 1 ; i < length ; i++){

value[i] = weight[i]-1;

total[i] += value[i]+weight[i];

}

}

and the corresponding, relevant, assembly code below. Note this time the compiler was able to vectorize the code.

0x100002050 <+416>: movdqu xmm1, xmmword ptr [rbp + 4*r10 - 0x4040]

0x10000205a <+426>: movdqu xmm2, xmmword ptr [rbp + 4*r10 - 0x4030]

0x100002064 <+436>: movdqu xmm3, xmmword ptr [rbp + 4*r10 - 0x2040]

0x10000206e <+446>: paddd xmm3, xmm1

0x100002072 <+450>: paddd xmm1, xmm0

0x100002076 <+454>: movdqu xmm4, xmmword ptr [rbp + 4*r10 - 0x2030]

0x100002080 <+464>: paddd xmm4, xmm2

0x100002084 <+468>: paddd xmm2, xmm0

0x100002088 <+472>: movdqu xmmword ptr [rbp + 4*r10 - 0x6040], xmm1

0x100002092 <+482>: movdqu xmmword ptr [rbp + 4*r10 - 0x6030], xmm2

0x10000209c <+492>: paddd xmm3, xmm1

0x1000020a0 <+496>: paddd xmm4, xmm2

0x1000020a4 <+500>: movdqu xmmword ptr [rbp + 4*r10 - 0x2040], xmm3

0x1000020ae <+510>: movdqu xmmword ptr [rbp + 4*r10 - 0x2030], xmm4

0x1000020b8 <+520>: add r10, 0x8

0x1000020bc <+524>: cmp r10, 0x7fd

0x1000020c3 <+531>: jne 0x100002050

In both cases, I used clang 7 with a simple -O3 as optimization argument.

The full example code can be found here.

As always, none of this matters if we don’t measure the results :) This is what Google benchmark has to say about our two examples (check out this post for how to use Google benchmark)

----------------------------------------------------------

Benchmark Time CPU Iterations

----------------------------------------------------------

calculate 1827 ns 1818 ns 394544

calculateVec 571 ns 568 ns 1192037

Not bad, the vectorized version of the code is over 3x faster on my computer (Broadwell Intel - 5th Generation).

The vast majority of time, we can get better performance by using the vector processing units in the backend.

The only reason I’m reluctant to say auto-vectorization is always better is because there are always specific, some cases in which that is not true. If you suspect there is a performance problem, the only way to know if that is better or not for you is by measuring the performance of both versions of the code. Both clang and gcc have flags to disable auto-vectorization.