Microbenchmarking C++ code

We don’t need to microbenchmark our application. Except when we find out we do.

In the interest of making the best use of our time, let me start by saying that microbenchmarking code - any code - can quickly have us spiraling through a very frustrating rabbit hole.

However, so long as we all understand that and the fact the benefits of optimizing code decrease very quickly with the size of your universe - e.i less code == more pain and less gain - then we can make the best of it.

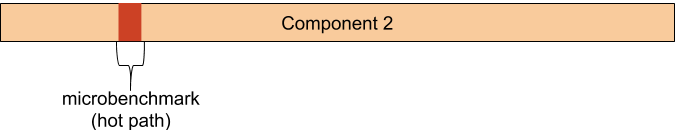

If your day job is trying to write code, critical code, where the accepted latency is in measured microseconds, then you’ll inevitably find yourself having to microbenchmark a piece of code. Most likely the hot (critical) path in the application.

Results are what really matter

Let’s imagine I need to make my high frequency trading application perform a few microseconds faster. Time is indeed money in this case. I can optimize and tweak all the code I want and even be able to make some of that code substantially faster.

However, if the overall processing time, from data received until a trade is made, doesn’t get me more and correct trades, the benefits can be, let’s say, contestable.

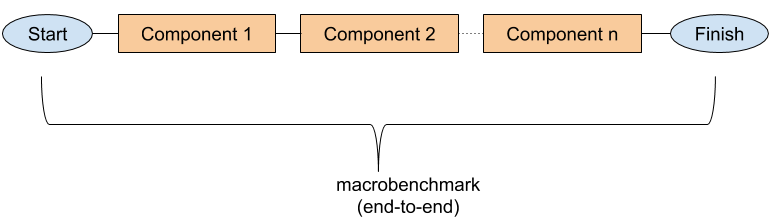

That’s why we always need to measure the overall performance of the system, from end-to-end, wire-to-wire, from packets arriving in the network card to an order being put on the exchange or a frames rendered on the screen (if games are your thing).

Macrobenchmarking is vital, make no mistake

The three important things: measure, measure and measure

Say after I benchmark my entire system, I found the hotspot to be a specific algorithm in one of the components. What do I do?

I get on to thinking of a solution and I have to benchmark my changes. But, not so fast.

No matter what you do, before starting changing code, measure it well and continue measuring throughout the process.

There are many ways to approach benchmarking and measurement and we’ll look into that in another article. Right now, we’re going to look into benchmarking a portion of the code (hence microbenchmarking).

Microbenchmarking with Google benchmark

In this article, we’ll be using Google Benchmark, a fantastic microbenchmarking framework for C++. I’m not going to cover all of its features but hopefully the majority of the common use cases. The project’s page on github is very well documented and I recommend reading it once you’re comfortable with the basics.

In addition to Google benchmark, I’ll be using clang 7, lldb and objdump for compiling and analyzing the generated assembly code.

To start with, follow the install instructions on the Google benchmark project page. The easiest steps at the time of this writting would be

git clone git@github.com:google/benchmark.git

mkdir build && cd build

cmake .. -DBENCHMARK_ENABLE_GTEST_TESTS=OFF -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=RELEASE

This will create a libbenchmark.a file that together with the include directory, it’s all we’ll need in our examples

The (very) basics

I’m going to start with an extremely simple tha will also help us understand what the compiler is doing with our code.

#include <benchmark/benchmark.h>

static void BM_simpleTest(benchmark::State& state) {

for (auto _ : state){

// intentionally do nothing

}

}

BENCHMARK(BM_simpleTest);

BENCHMARK_MAIN();

So the code is, well, simple; BM_simpleTest is the function we want to measure and needs to have the signature the framework recognizes.

BENCHMARK() registers the functions we want to benchmark while BENCHMARK_MAIN() uses the framework built in main function to execute the code.

The output on my Macbook Pro is

Run on (4 X 2700 MHz CPU s)

CPU Caches:

L1 Data 32K (x2)

L1 Instruction 32K (x2)

L2 Unified 262K (x2)

L3 Unified 3145K (x1)

Load Average: 2.32, 2.42, 2.71

--------------------------------------------------------

Benchmark Time CPU Iterations

--------------------------------------------------------

BM_simpleTest 0.000 ns 0.000 ns 1000000000

Note the information in the begining of the report. It can be very useful for understanding the conditions in which the code is executing. For example, my computer has 4 cores but 2 unified L1 cache, which means it’s shared by 2 execution cores. This processor has 2 actual cores plus 2 with hyperthreading.

Also, not how fast the code run, 0 nanos :) amazing. That’s because it’s not doing anything.

Let’s look at the assembly output of the generated code. For that, I’m using lldb set for the Intel idiom.

The code was compiled with clang 7, and the flags -O3 -g -fno-exceptions -fno-rtti -mno-omit-leaf-frame-pointer -fno-omit-frame-pointer.

0x100001430 <+0>: push rbp

0x100001431 <+1>: mov rbp, rsp

0x100001434 <+4>: push rbx

0x100001435 <+5>: push rax

0x100001436 <+6>: mov rbx, rdi

0x100001439 <+9>: call 0x100001ab0 ; benchmark::State::StartKeepRunning()

0x10000143e <+14>: mov rdi, rbx

0x100001441 <+17>: add rsp, 0x8

0x100001445 <+21>: pop rbx

0x100001446 <+22>: pop rbp

0x100001447 <+23>: jmp 0x100001b80 ; benchmark::State::FinishKeepRunning()

0x10000144c <+28>: nop dword ptr [rax]

You don’t need to really know assembly for this, I just want to display the boundaries of the benchmark execution code, and its contents. The generated assembly doesn’t have anything in it, as expected. That explain the benchmarked code taking 0ns to run.

Back to the benchmark output, note the column Iterations. That shows the number of times the code had to be executed until an stable value was reached. This library does some amazing things to try and find the most stable result set.

As you can imagine, there could be a lot of variance in microbenchmarking and the tail, is something very dangerous and critical to be considered. I’ll talk more about that in another post.

Let’s try another case, say we want to measure the time it takes to increment a single variable

#include <benchmark/benchmark.h>

static void BM_simpleTest(benchmark::State& state) {

for (auto _ : state){

int x = 42;

x++;

}

}

BENCHMARK(BM_simpleTest);

BENCHMARK_MAIN();

The output being

--------------------------------------------------------

Benchmark Time CPU Iterations

--------------------------------------------------------

BM_simpleTest 0.000 ns 0.000 ns 1000000000

Still 0 nanoseconds, which maybe correct but it is suspicious. Let’s look at the assembly code again

0x100001480 <+0>: push rbp

0x100001481 <+1>: mov rbp, rsp

0x100001484 <+4>: push rbx

0x100001485 <+5>: push rax

0x100001486 <+6>: mov rbx, rdi

0x100001489 <+9>: call 0x100001ac0 ; benchmark::State::StartKeepRunning()

0x10000148e <+14>: mov rdi, rbx

0x100001491 <+17>: add rsp, 0x8

0x100001495 <+21>: pop rbx

0x100001496 <+22>: pop rbp

0x100001497 <+23>: jmp 0x100001b90 ; benchmark::State::FinishKeepRunning()

0x10000149c <+28>: nop dword ptr [rax]

It looks exactly like the previous one, where we had an empty loop. You probably already guessed what is going on, the compiler is optimizing away the code we wrote. And we do want the optimizations on.

Thankfully, Google benchmark has a solution for that, a nice little trick in the form of the method benchmark::DoNotOptimize()

Let’s add that to our code

static void BM_simpleTest(benchmark::State& state) {

for (auto _ : state){

int x = 42;

x++;

// here we tell the compiler that may be used by other cpus

// so don't eliminate it just yet

benchmark::DoNotOptimize(x);

}

}

The output this time is

--------------------------------------------------------

Benchmark Time CPU Iterations

--------------------------------------------------------

BM_simpleTest 0.331 ns 0.330 ns 1000000000

That’s more like it, pretty fast but not zero. Let’s look at the assembly code again. Last time, I promise you.

0x10000144d <+13>: mov r15b, byte ptr [rdi + 0x1a]

0x100001451 <+17>: mov rbx, qword ptr [rdi + 0x10]

0x100001455 <+21>: call 0x100001ab0 ; benchmark::State::StartKeepRunning()

0x10000145a <+26>: test rbx, rbx

0x10000145d <+29>: je 0x10000147c ; <+60> [inlined] benchmark::State::StateIterator::operator!=(benchmark::State::StateIterator const&) const + 5

0x10000145f <+31>: test r15b, r15b

0x100001462 <+34>: jne 0x10000147c ; <+60> [inlined] benchmark::State::StateIterator::operator!=(benchmark::State::StateIterator const&) const + 5

0x100001464 <+36>: nop word ptr cs:[rax + rax]

0x10000146e <+46>: nop

0x100001470 <+48>: mov dword ptr [rbp - 0x1c], 0x2b ; this where our variable is initialized and set

0x100001477 <+55>: dec rbx

0x10000147a <+58>: jne 0x100001470 ; <+48> at MicroBench.cpp

0x10000147c <+60>: mov rdi, r14

0x10000147f <+63>: call 0x100001b80 ; benchmark::State::FinishKeepRunning()

0x100001484 <+68>: add rsp, 0x8

There’s a lot more going on this time, we can see the framework’s code for state tracking present as well as our own code at address 0x100001470. Note it’s set to 0x2b which is 43. Our friend compiler took the liberty to initialize the variable to its final value.

The method benchmark::ClobberMemory() can also be used to get around compiler optimizations but this one will create a memory barrier and force all variables to be written to memory, which may not be what you want at all times so use it carefully.

Let’ look at a another feature in a little more elaborate example.

static void BM_simpleTest(benchmark::State& state) {

const int length = 2048;

int values[length];

// populate values

unsigned long x = 0;

for (auto _ : state){

for(int i = 0 ; i < length ; i++){

x += values[i];

}

}

benchmark::DoNotOptimize(x);

}

BENCHMARK(BM_simpleTest);

We just to want to add all the numbers in an array, ignoring the potential overflow. Note we left the initialization of the array outside the state loop to avoid adding that to the final result, since all we care about is the time it takes to scan the array and add to our accumulator.

Let’s say we want to do the same but for several different lengths of values. We can do that by calling with arguments.

We can pass parameters to our code by invoking the method Arg() in the object returned by the BENCHMARK(). This can be done multiple times and each time will execute our benchmark test with a different parameter.

Let’s tweak our code a bit to make that work

static void BM_simpleTest(benchmark::State& state) {

const int length = state.range(0);

int* values = new int[length];

// populate values

unsigned long x = 0;

for (auto _ : state){

for(int i = 0 ; i < length ; i++){

x += values[i];

}

}

benchmark::DoNotOptimize(x);

delete[] values;

}

BENCHMARK(BM_simpleTest)->Arg(1 << 2)->Arg(1 << 3)->Arg(1 << 5)->Arg(1 << 10)->Arg(1 << 15);

state.range(0) contains the arguments being passed to our benchmarking function. The Arg method allows passing multiple parameters, each returning in a different index in range.

The output of this execution is

--------------------------------------------------------------

Benchmark Time CPU Iterations

--------------------------------------------------------------

BM_simpleTest/4 1.96 ns 1.96 ns 356206905

BM_simpleTest/8 2.61 ns 2.61 ns 268194096

BM_simpleTest/32 6.92 ns 6.90 ns 95709481

BM_simpleTest/1024 179 ns 179 ns 3904790

BM_simpleTest/32768 6011 ns 6000 ns 112604

Note how less iterations are required to get to a more stable run.

That’s it for now, for more information about the tools used in this articles, see: